I generally consider myself to be risk-averse.

I have full insurance coverage on my car, I don’t take jobs on contract or with tiny start-ups which are likely to fail within the next year, and I keep my money in low-risk mutual funds. I’m also well aware of how hypocritical that reads given that I spend copious amounts of time on the racetrack with my daily driver. Somehow, I’ve managed to convince myself that the performance driving I do is generally safe. That’s because aside from a handful of corners, most local tracks feature low speeds, are generally void of walls, and feature plenty of grassy run-off.

Our local watering hole – the Toronto Motorsports Park – is a good example. All corners feature apex speeds below 100kph, and there’s just one corner that’s adjacent to a wall: the slow right-hander leading onto the front straight. I watch a dozen people go flying off the track every time I’m there. For better or for worse, nobody bats an eye. You look over your car, figure out what you did wrong, and head back out there.

Ontario Time Attack

I’ve basically dedicated this year to a local time attack series called Ontario Time Attack, for the main reason that it’s the only time attack series that doesn’t require an obscene amount of money in order to be competitive. That’s because there’s a problem with time attack: it isn’t spectator-friendly. In other words, it’s boring to watch.

You won’t find the wheel-to-wheel action of touring-car racing, nor the drama, noise, and tire smoke of drifting. That’s obviously bad news for organizers because spectators bring in revenue, allowing them to rent massively expensive venues. To deal with that, Time Attack series usually do two things: run-time attack events alongside drifting and/or touring car racing (I.e.; Gridlife) and structure their classes to encourage drivers to show up with ridiculously modified, insanely fast cars. Because let’s be honest, nobody wants to watch me lap Road Atlanta in a stock FRS; they want to see James Houghton topple lap records in his 800hp Integra.

For that reason, Time Attack series like the Canadian Sport Compact Series (CSCS) and Gridlife lump most four-and-six-cylinder cars into a single “production” or “street” class while allowing for a generous range of modifications. In Gridlife Street (the slowest class), short of upgrading turbo-chargers, adding aero, or performing significant weight reduction, almost anything goes. This means my little FRS ends up competing against 370Zs with built motors, Civic Type Rs, Subaru WRX STis – you get the picture. OTA is special because it’s classes are designed to allow anyone to enter with anything, and end up in a class where they’ll be competitive. Toyota Echo? Stock FRS? Caged and gutted STi? There’s a unique class for that.

Ontario Time Attack is how I ended up on the paddock of the famous Canadian Tire Motorsport Grand Prix circuit. Because frankly, if I weren’t trying to nab every point possible in a desperate attempt to bring home a championship trophy, I wouldn’t be here. That’s because the track formerly known as Mosport GP is properly terrifying.

Mosport GP

A bit of history; it’s one of the few tracks on the planet to have hosted Formula 1, Indycar and Nascar in its 60-year history. It has the honour of being one of the fastest racetracks on the planet. And it’s speed isn’t manifested in one mammoth straight like Road Atlanta. Mosport GP is all about apex speed. Street cars like mine regularly see 150kph mid-corner.

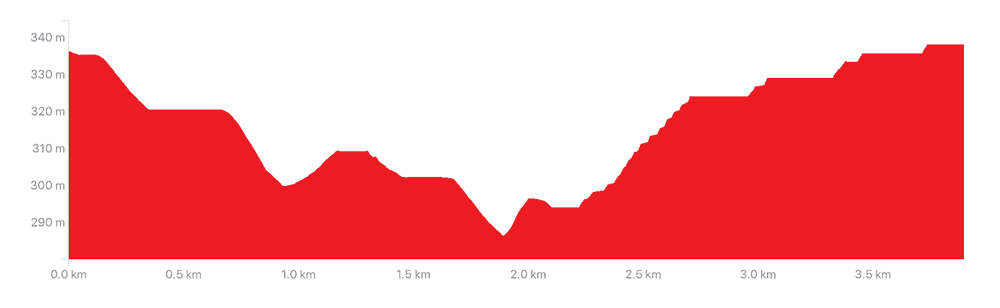

Then there’s another challenge: massive elevation change. In total, the circuit features 56 meters of elevation gain which appear in giant sweeping plunges. Come over the crest entering turn two and you’re greeted with a 20-meter drop from entry to exit. Turn four is similar; a blind, high-speed downhill left-hand turn that throws you into a deep braking zone before the slowest corner of the track. Huge drops in elevation through a corner do two things: initially, they make the car light and skittish, precisely where you need grip most: braking and turning. Couple this with high-speed and small mistakes can get expensive very quickly. As the ground rises the suspension settles, the car is pushed into the tarmac creating a shocking amount of grip. In the case of Mosport GP, the ground rises up just as you’re breaking into turn five, allowing you to brake incredibly late. That’s a good thing because there’s very little time between the exit of turn four and the entry of turn five. Braking over a crest, mid-corner while the car is light and unloaded, is deadly.

I use such dire language because there’s another problem with Mosport GP; there’s very little runoff. As a result, most off-track incidents involve impact with a wall. I’ve been to Mosport a total of four times. In that time, I have seen five off-track incidents, three of which resulted in the car being sent home on a flatbed.

I was on track for one such incident. Mid-way through the back straight, marshalls start furiously waving red flags. Myself and the traffic around me come to a stop by a nearby a marshall station for what feels like an eternity. Sitting there, I catch a message from my friend and teammate Daniel, asking me if I’m okay. It’s at that moment that I realize someone’s gone off, and that somebody could have been me. Eventually, we get off track and into the pit lane, passing the crumpled wreckage of Acura Integra that ended up nose-first into the wall outside of turn-nine. Back in the paddock, I resisted the urge to throw up. The driver walked away shaken, but otherwise fine. The car was totaled.

Fear

All of this presents a unique problem: fear. Because massive and sudden changes in elevation, blind corners, and imposing walls all require an immense amount of confidence to attack. More so, they requires impeccable accuracy and smoothness. Traits that just aren’t compatible with fear. In short, this requires complete acceptance and acknowledgment of the risk that you’re taking on. It requires getting out of your own head. I struggled with this all weekend.

I’m constantly reviewing data while in competition; I’m that weirdo analyzing speed traces on my MacBook in the paddock like Jesse from the Fast and Furious. That’s because I’ve realized that progressing from driving slow laps to moderately quick laps, is pretty easy with a little instruction. However, going from moderately quick laps to blisteringly fast, trophy-winning laps? That requires a secret sauce: data. Only data can tell you that you held the brakes for slightly too long, causing you to over-slow by 5kph during corner entry compromising the entire following straight and losing three-tenths. Little mistakes each corner add up, costing you seconds each lap.

Not only does data help you go faster, but it also makes you more consistent. Your best lap will become a blueprint for a ‘fast lap’. From there on out, you can compare every other lap to your best to figure out where you’re losing pace. In a time attack setting, being able to answer the burning question of “where am I losing time?” is invaluable. Better yet, if you can find some friends who are willing to share data with you, you can literally pinpoint exactly where they’re faster.

Back to Mosport. After each session at Mosport GP, I’d start reviewing data. Where am I over slowing on entry? Where am I inconsistent with throttle? How do I go faster? I’d make a mental list of three things to improve on. Then I’d go out, and do the exact same session, just a little more polished. Same entry speeds, same lap times. That’s because saying “I need to brake less” entering corner X, and actually doing that when the world is flying past you at 160kph are two very different things. Fear is a paralyzing force.

The best advice I’ve gotten on this topic starts with this: remind yourself of the things you know. You know that abruptly lifting mid-corner is a great way to upset the balance of the car – so don’t do it. Stabbing the brake pedal is even more egregious. You also know that, if the car isn’t sliding or understeering, the tires are happy and gripping, so why lift? In short, you understand the physics: don’t allow fear to let you do something that is irrational. The worst thing you can do is get intimidated by the speed you’re carrying, do something silly to try and bleed said speed, and get yourself into real trouble.

To follow up on that advice: commit to each input. If you’re accelerating out of a corner, apply the throttle smoothly and keep your foot in it. If you feel the need to lift because you’re going wide on corner exit, you’ve made two mistakes: first, you’ve apexed too early. The second, and more important mistake, is that you failed to recognize that you’ve apexed too early, and you didn’t account for it when introducing throttle.

As an amature driver learning a track, this means being conservative. Braking earlier and harder going into a corner, and getting on the gas later and apexing later on exit. Then slowly, one corner at a time, start pushing little-by-little and listen to the car. Push your braking point a little, get on the gas a little earlier, and let the car drift wider on corner-exit.

If fear is keeping you from braking later, try braking at the same spot, but with less pedal pressure. The result is the same; more corner entry speed, but it’s an easier leap mentally.

Having trouble getting on the gas early? Remind yourself of the physics; if you’re understeering on exit, then you’re probably getting on throttle too early. If you’re not, you know you can start feeding in throttle earlier. If the car is happy, that’s a very good sign that you should be on the gas earlier.

Obviously there’s a lot more to take into account; your line, how you’re managing weight transfer under braking, when and how quickly you’re feeding in steering. But the point is; whenever you introduce any input, commit to it.

The best racing drivers make mistakes all the time. The thing that separates the great from the mediocre isn’t just that they make less mistakes. It’s that they recognize their mistakes and correct them earlier. There’s a lot to be said on this topic, but the moral of the story is to work on recognizing your mistakes early and adjust your inputs accordingly. That way, when you add throttle, feed-in steering or brake, there will be no hesitation because you got the timing in the first place. Smoothness is everything. And at a track like Mosport GP, smoothness is mandatory.

Performance driving isn’t something that comes naturally to most people. I vividly remember sitting in the passenger seat of a friend’s NB Miata at my first autocross thinking to myself that I didn’t know cars could do this. Autocross, track days, time attack; it’s all inherently uncomfortable at first. You’ll fumble around the track getting passed by everyone, you’ll probably end up in grass at some point, and it’s probably going to be embarrassing. But in that discomfort comes growth. More so, I would argue that getting to the point where you can turn reasonably quick laps around your local circuit is just the beginning. Adaptability is a skill that autocrossers pride themselves in. Learning new tracks allows track-drivers to exercise that same skill. And in the process, you’ll refine your inputs and become more consistent – especially in an environment that forces you to: Mosport GP. Yes, it’s higher risk than most, but with a little patience and discipline, you can manage that risk. And in that process, comes growth.

Cover photo by the talented Dimitry Mochkin (@dimitry_om)

Special thanks to Kevin Wong for his mentorship, coaching, and for inspiring this piece.