This is Part 2 of our multi-part series called “How to Win a Time Attack Championship”. You can read Part 1 here.

Daniel and I started buying parts in the fall. That’s when we both made the same mistake: buying used coilovers. Quality street coilovers are, generally speaking, expensive. When it comes to coilovers designed for track use, even more so — quite often exceeding the $5000 mark. So when you’re building a competitive track car on a budget, picking up a ‘lightly used’ set on Kijiji can be mighty tempting. But with everything cheap short of a ’99 Corolla, you’re compromising reliability. Dampers are a sensitive combination of rubber seals, oil, and compressed gas. Over time, they leak, lose pressure, and generally fail to do the job that they’re designed to do: dampen. If your idea of ‘performance driving’ involves sprinting down a backroad, this isn’t overly concerning. But if you intend to spend your weekends jumping curbs at your local racetrack, well, keep reading.

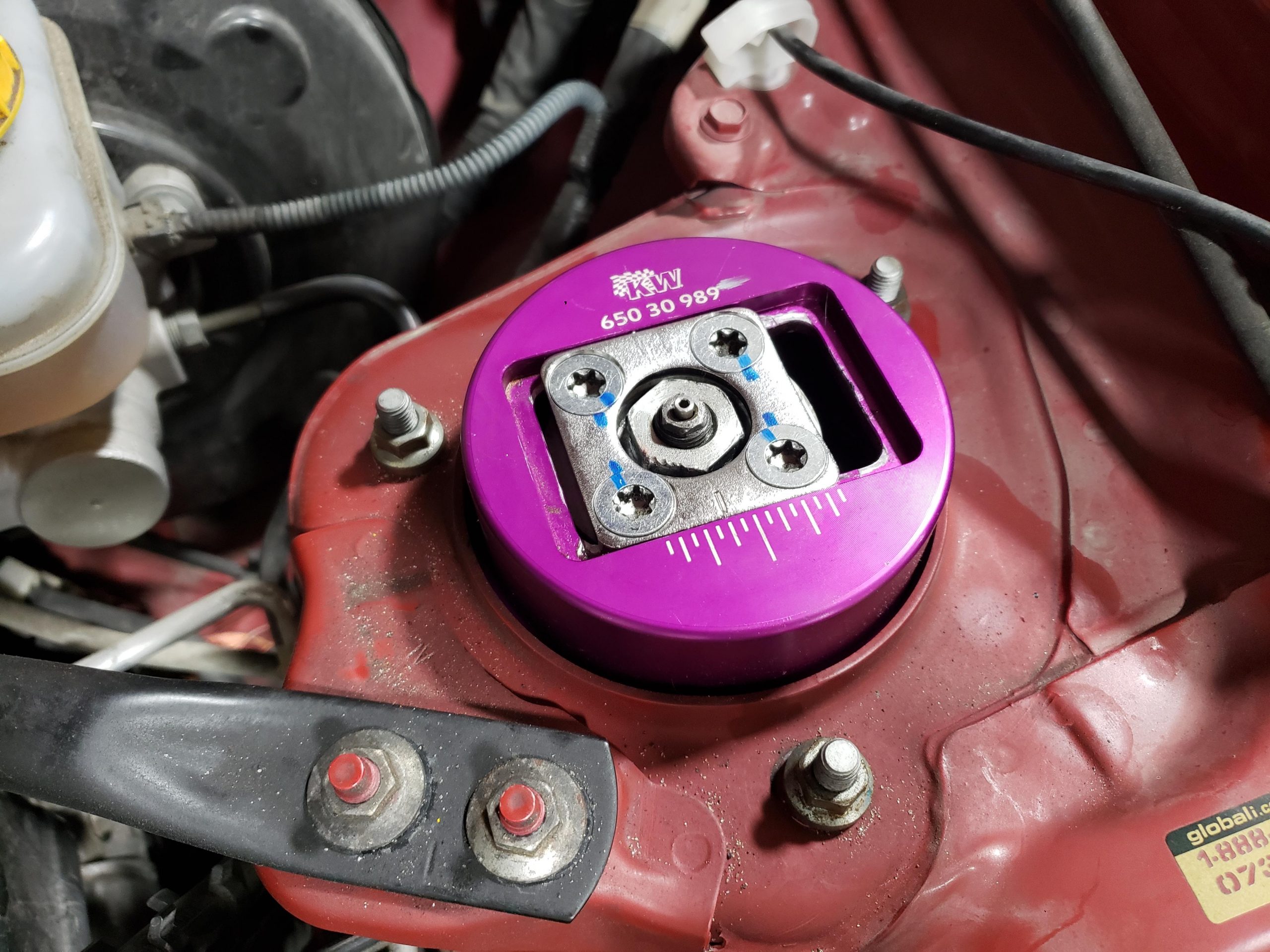

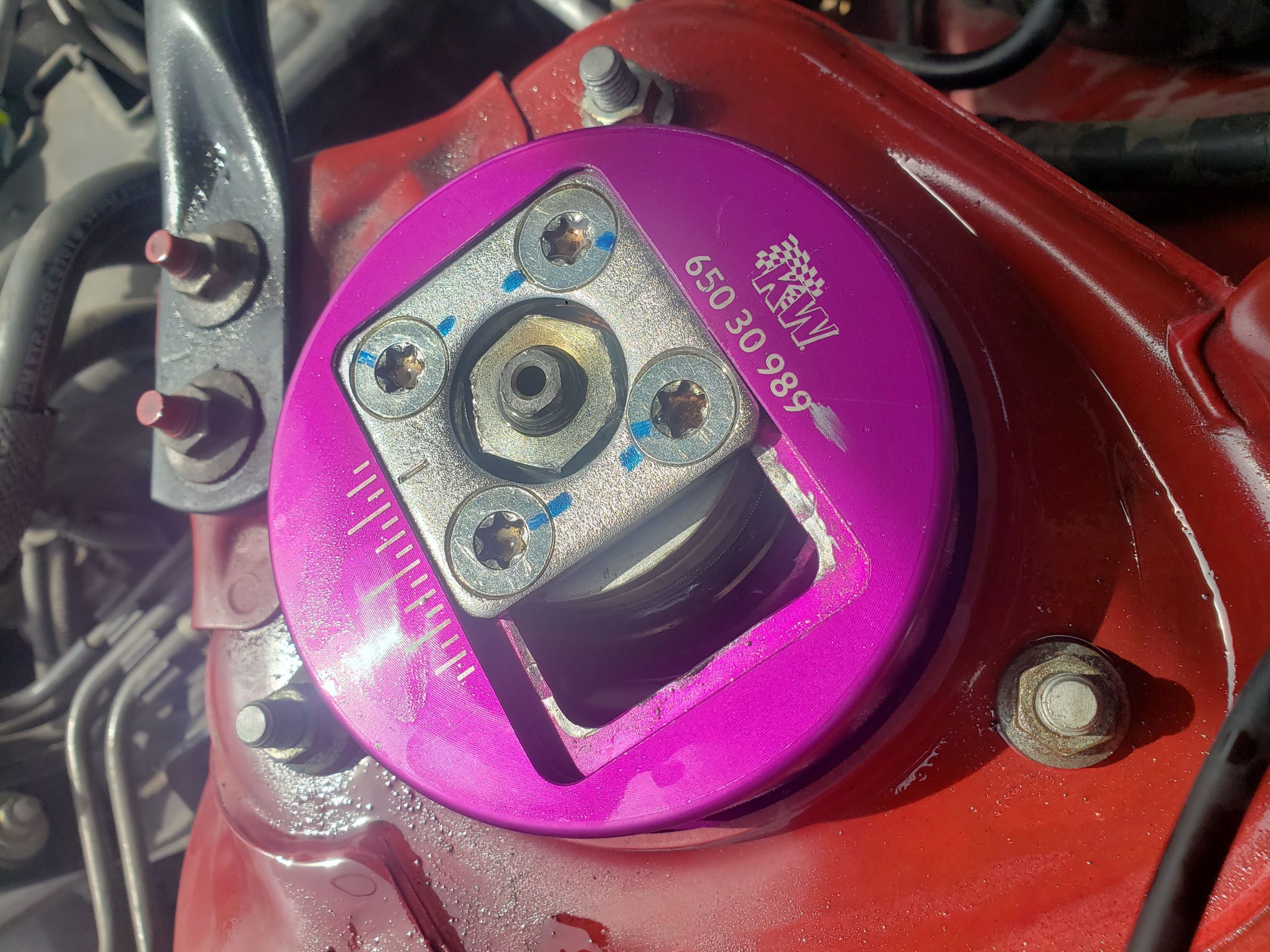

This is precisely what I wasn’t thinking when a set of KW V3s popped up on Facebook Marketplace. They looked clean, supposedly had just 2000 KMs on them, and came with a set of KW Clubsport top hats, all for $2000. I took the bait, and the next thing I knew I was standing in a Tim Hortons parking lot next to a chain-smoking twenty-something, waiting for an etransfer to go through. With my new-to-me KW V3s in hand, I was giddier than a kid on Christmas morning. That was until a post popped up on Facebook a few days later, alleging that the same person who sold me my coilovers had pulled them from a car that they’d crashed at Shannonville. I was the proud owner of very questionable, warranty-free goods.

Upon seeing that post, I reinspected my KWs and not only confirmed that the allegations were true, but that signs were obvious enough that not noticing them during my pre-purchase inspection was inexcusable. One of the brackets on the passenger-side front strut was bent and a rear-top hat was missing entirely. Trying to make the best of the situation, I had XIII Motorsports fix the bent bracket and replace the missing top hat with a brand-new unit from KW. I also decided to increase my spring rates using new Swift springs. By the time the struts were ready for install, I’d spent over $3000 on used KWs. Daniel’s story is less dramatic. He knew what he was buying, but what he bought was a tired and rusty pair of last-generation AST coilovers.

With our parts, though questionable, in hand, it was time to start prepping the cars. Daniel’s car received the full Whiteline treatment, meaning all control arm bushings were replaced with Whiteline’s line of synthetic rubber bushings. These bushings split the difference between traditional poly bushings and factory bushings. Unlike factory bushings, they’re two-piece – meaning that rubber bushing rotates around its metal sleeve allowing the control arm to move freely, without the disadvantages of poly bushings which require periodic lubrication and have a tendency to become brittle and crack over time. Slop was eliminated from the drivetrain using a combination of Cusco engine mounts and Whiteline differential and transmission mount inserts.

Both cars received Whiteline adjustable sway bar endlinks. Those would later allow us to add sway bar stiffness to either side of the car on the fly, without modifying the sway bar itself (doing so is illegal in our class). Finally, I had to do something about the FRS’ driver’s seat. Most people are surprised how aggressively bolstered the FRS’ stock seats are, and opt to continue using them in a track environment. That becomes a problem as you get faster because you’ll find yourself putting a lot of effort into bracing against the door and transmission tunnel with your knees. I opted for the Recaro Profi SPG. Why? I’m a skinny dude and it’s one of the few seats I’ve tried that fits me snuggly while being superbly comfortable. It’s honestly the best seat I’ve ever sat in. Something to know about Daniel; “street comfort” isn’t in his vocabulary, so he opted for the hyper-aggressive OMP HTE-R – halo and all.

Finally, Richard got both cars prepped, aligned, and corner balanced, and we were ready to hit the race track. That’s when Daniel’s coilover-troubles started. His ASTs started leaking shock fluid almost immediately after he started street driving. Why? According to Paragon Performance, the shop that ended up rebuilding Daniel’s coilovers, his 4150-series coilovers were just old; they’d been replaced by the 5100-series years ago and were no longer in production. Rebuilding the ASTs was going to take weeks, so Richard swapped Daniel’s car back to stock suspension in the meantime and we hauled the cars out to the Toronto Motorsports Park for the first event of the year: Northern Speed Time Attack’s season opener.

Northern Speed served as practice for the upcoming OTA event at DDT, a chance for myself, Nathan and Daniel to shake off the rust that we’d built up over the winter, and to make sure the cars were actually fast. The latter was more important to me than for Daniel, because after all, his car was effectively stock.

There was a sense that we were starting something special that morning in the paddock. After months of lockdown, being out at our home track and surrounded by people I now referred to as “teammates” was glorious. Richard was running around getting the cars loaded up with all-important Ry Spec decals, along with setting each car’s base tire pressures and shock settings. At the same time, I prepped my new-to-me data acquisition setup: a RaceCapture Track Mk2. It’s a budget-friendly unit that allows me to capture 10 hz GPS position data, along with lightning-fast canbus data straight from the car’s OBD port. This would later prove useful in determining what I was doing with the throttle or brakes, that caused the car to react in a certain way.

The plan for the day was simple: we’d each head out on track, rip some laps, and intentionally drive a very-fast ‘cool down’ lap so that when we rolled into the pits, our tires were still hot enough to get accurate ‘hot’ tire pressure readings. This meant going easy enough on brakes that they’d still have adequate time to cool, while keeping speeds up during cornering. Then we’d debrief with Richard. Was the car understeering? High speed or low-speed understeer? What were you doing when the car started understeering? Then he’d adjust tire pressures and shock settings accordingly. With each session, the balance of the cars would shift back and forth with the ultimate goal of perfect balance. It was the closest I’d ever felt to being on a real race team.

Trouble started early on Nathan’s high-strung Subaru WRX STi. Specifically, he couldn’t seem to keep power steering fluid, in the power steering pump. He’d go out, lay down a few laps, and roll into the pits spewing out power steering fluid. To their credit, Richard and Nathan spent a considerable amount of time rolling around underneath the moist Subaru trying to seal the leaky pump with silicon, but that proved futile. Knowing when to call it quits, the car was loaded onto a trailer to drive another day.

Moving on to my car: initial impressions of the modified KW V3s were good: turn-in was effortless and sharp, the car felt stable and composed at the limit and cornering was noticeably flatter. My only handling qualms pertained to the car’s ability to send power to the ground on corner exit: it was very prone to power-on oversteer, though, in retrospect, that probably had more to do with old tires, than the car’s suspension. I was still on the Hankook RS4s I ran the previous summer.

That’s when a different, unexpected issue came up: my brakes. The car’s fresh brake rotors had warped in record time. Stepping on the brake pedal felt like stepping on a vibrator. The car pulled to the right and stopping distances got longer with each lap. I would later discover that I had installed my front-left caliper’s sliders slightly crooked causing one side of the pad to drag.

Lunch came and went, which meant it was time for competition sessions. Thanks to my shot brakes, I was slower than I’d been the previous summer bone stock. Any shot I had at the Northern Speed podium had by now, completely evaporated. But never being one to waste a lapping opportunity, I still took the car out, nonfunctional brakes at all. That’s when the day’s most expensive failure occurred.

I went out for a fairly uneventful session, came into the pits with my brakes smoking profusely. I didn’t think much of it initially given that we’d already established that my brakes were fucked. That was until I popped the hood to check my engine oil level, and noticed that shock oil was pooling in my driver’s side strut-mount. Upon further inspection, the rebound adjustment valve was gone, and the engine bay, wheel well, and yes, hot brakes, were coated in shock oil.

So I had three problems to sort out before the first Ontario Time Attack event — brakes, tires, and blown suspension. Oh, and I cracked my front bumper hitting a cone. On the bright side, Daniel and I now had matching drift-stitches.

None of this was surprising. I’ve been around long enough to know that tossing stiff springs on coilovers that were involved in an accident, is almost certainly going to lead to heartbreak. But I was chasing losses — just like I did with my catastrophic Ecotec Miata. Trying to throw money at a problem that impulsivity had caused. It was time to stop. I briefly considered getting the blown KWs shipped out to California for a rebuild, but had I done that, I would have still been trying to make an un-ideal suspension setup work on the racetrack. The KW V3 isn’t a motorsport coilover. It’s a street-performance coilover that comes standard with incredibly soft springs. There is a reason the KW Clubsport exists; and I wasn’t about to drop five-grand on Clubsports. It was time to go back to the drawing board.

With just a week to go before the first OTA event of the season, I decided to toss stock struts and springs back on the car and compete in OTA’s GT4 class instead. Solving the car’s braking issues was a simpler task — a fresh set of Gloc R10s and blank rotors went on the car and we were good to go. Finally, the well-worn Hankook RS4s were swapped out for a fresh set.

Turning our attention back to the STi — Nathan’s power-steering woes had a simple fix. His power-steering leaks were a result of overheating power steering fluid. He spliced in a simple two-row radiator and voila: no more overheating power steering fluid.

Daniel to his credit, had a much better day than all of us. After all, he was effectively driving the same car he’d driven last year, just with new bushings and a proper seat. He managed to drive his way to a second-place finish, which was impressive given that he was sharing a class with Civic Type-Rs, Golf Rs and BMWs (cars like this would later be moved to a separate “Street Plus” class). I was proud of him, albeit a little jealous. That said, losing as a result of a mechanical failure is always easier than losing because you let yourself down. That’s a lesson I’d soon learn the hard way.

This is part two of a multi-part series. Click here to read part 3!