This is Part 5 of our multi-part series called “How to Win a Time Attack Championship”. You can read Part 4 here.

In popular culture, most depictions of car-people in relationships fall into one of two buckets. Half the time, car-culture is the glue that holds the relationship together. They wrench together, drive together, they’re seen at every event together. This couple got engaged at a dragstrip, or during an autocross, or maybe at a track day, you get the picture. For other couples, it’s a prybar tearing the two of them apart. One partner complains about their partner’s spending, the time spent away, while the other struggles to balance their two loves. Either scenario makes for great television.

For me and my wife Tabrina (and for most people, I assume), things aren’t quite that dramatic. She couldn’t care less about racing, but respects the passion. She does, however, like going fast. For that reason, she’ll join me for the occasional track day and ride shotgun while I rip laps. Opportunities to do that are few and far between in the midst of an Ontario Time Attack season. Competition events are not particularly passenger-friendly, and practice days are usually a fury of tire pressure checks and data review.

We did however finally manage to get out to a quiet lapping day together. It was an event hosted by Pinnacle Advanced Driving Academy at the Toronto Motorsports Park. I hadn’t been back to TMP since I got my butt kicked at the first Northern Speed event of the season and I needed to find my pace again.

If you’ve never been to a PADA track day, they cater to less experienced drivers in high-horsepower cars, after all, PADA is an advanced driving school. But with on-track instruction not being viable in a post-Covid world, they’ve taken to organizing quiet, well-run weekday track events instead.

That also means that this is one of those events that will go straight to your head if you’re not careful. Within two sessions I passed a Corvette C7 Z06, which prompted the owner to walk over to me later and exclaim “wow you’re driving the shit out of that car!”. Tabrina usually gets a kick out of that. Moments like that force me to review my lap times and remind myself that I’m not a driving god, I’ve just driven this track a thousand times. Ego is the enemy.

It was at this point that my historically reliable Scion FRS, also decided to remind me that I’m not infallible. On my third session out, the entire catback fell off the car. I ended up dragging it from the apex turn-nine all the way back to the pits. This was my fault: I noticed a while ago that my muffler was only being held to the chassis by two out of the four exhaust hangers. Presumably, the previous owner had a muffler delete (like every FRS) and got lazy reinstalling the old muffler. And to be fair, that held together for two years. Back in the pits, I did the only reasonable thing I could: reinstall the exhaust on the hangers, add a zip tie for good measure, and get back on track.

Two laps into the next session on nearly the exact same corner – bang. The exhaust hit the floor once more. Not only did my zip tie solution fail, but it also caused more carnage. The thin zip ties pressing against the soft rubber hangers cut one of them in half. With my entire catback now hanging off the car by just one hanger, it was time to call it quits. I ratchet-strapped the unsupported side of the muffler to the chassis and packed up my things. Tabrina didn’t mind getting home early – but having the car break during our only track day together was a little heartbreaking.

That’s when my problems got worse. As we were leaving the paddock the FRS started emitting a distinct squeal while the clutch pedal was depressed. I immediately knew my throw-out-bearing was failing. The throw-out-bearing is the FRS/BRZ/86’s Achilles’ heel, they fail on every car around 100,000 kms – it’s not a matter of if, but when. There’s also no real solution either, no revised part number, nothing.

This presented a serious logistical problem, because when the TOB in your twin fails, it fails fast – you have roughly 200 km from when it starts making noise before it’s undrivable. To make matters worse, the next OTA event was a meager four days from now. I limped the car home and started making phone calls. Calling Richard, our team race engineer, was uncomfortable. Mostly because I knew his schedule, and therefore I knew exactly what I was asking him to do: I was asking him to work hours into the night, after working a full-shift ar Radical, in order to get my car ready in the next few days. But he didn’t need much convincing, after all, my success on the racetrack reflects on him – his brand is slathered all over the car. Being ready for Mosport felt mission-critical – for both of us.

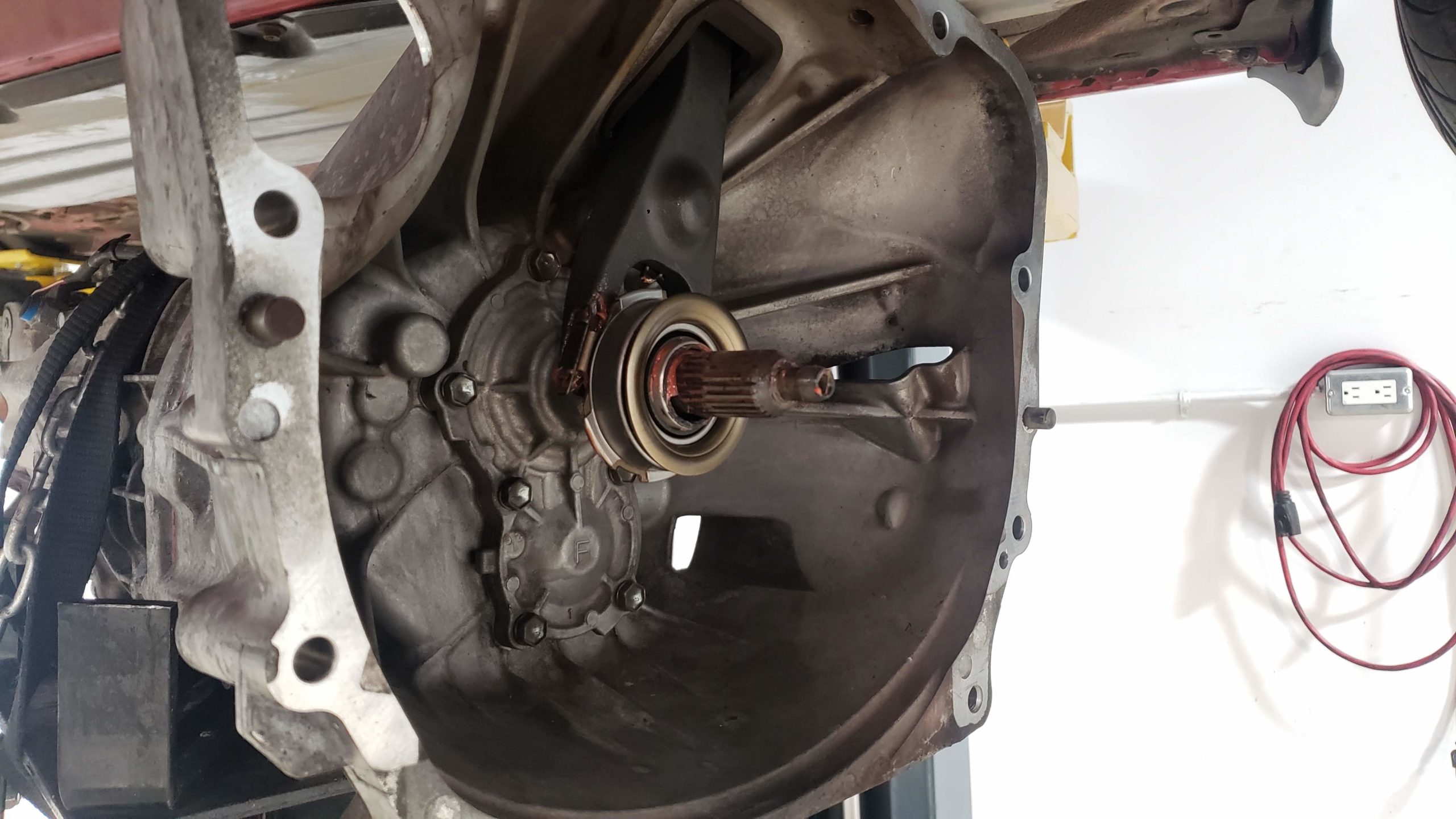

By the time I was pulling into Radical Canada East, the clutch was already slipping. Richard pulled the transmission out of the car over the next two days, working into the night. The throw-out-bearing was literally in pieces. I’m not entirely sure how the car drove into the shop under its own power. When ordering parts, I did the natural car-person thing, and spent an enormous amount of money under the guise of “future-proofing”. The OE clutch was replaced with Stage 3 Competition Clutch – a full face ceramic clutch capable of holding 300ft-lbs of torque, because, erm, reasons. A high torque clutch puts more pressure on the clutch fork and pivot bearing, parts that are already known for breaking on the FRS/BRZ, so I upgraded them to heavy-duty Cusco units.

My OE exhaust was in rough shape having been dragged at speed on concrete several times now – but all of my drivetrain “future-proofing” meant there wasn’t budget left for an new exhaust, so the mangled factory unit was installed with fresh hangers. With just a day to go before our Mosport weekend, the FRS was buttoned up and rolling out of Radial Canada under its own power. Our Mosport weekend was saved.

This got me thinking about the relationships we build with people, particularly technicians like Richard, and how they contribute to success on the racetrack. If you look closely at every successful time-attack driver, you’ll find a network. A network of specialty shops, suppliers, sponsors, and teammates. Nobody can do this alone: even if you’re a miracle worker who can fabricate, build engines, perform custom alignments, and most importantly, drive, there just aren’t enough hours in the day to do it all. Case in point – I’ve replaced clutches, I could have done this myself. But I also have a full-time job, and I could have compromised the car’s reliability.

Building a network is insanely important. You will need parts at the last minute, you will break things, and you will need help. This means building relationships with the people around you. And a lot of this is simple: pay your shop bills on time, refer them to your friends, and try and be flexible with timelines when you can.

The harder thing for most people, is resisting the urge to shop around. I’ll try and explain why that’s generally a bad idea. Say you need your bushings replaced. You’ve been going to Shop A for years – you tag them in your Instagram posts, hang out with them at the track, and run their sticker on your car – you have a relationship. They quote you $1200 to replace all control arm bushings. Shop B, a place that you’ve never been to, quotes you $1000 – so you bring your car there instead.

When you do this, you create two problems. First, you’re telling Shop A that you value everything they’ve done for you at less than $200. Secondly, shops prefer looking after a car in its entirety, so that they know the car’s history, and they know how it’s been taken care of – especially if their name is on it. Now let’s say something happens – a bushing cracks prematurely, a control arm bolt backs out on track because it was under-torqued. Shop A isn’t about to rearrange its schedule and inconvenience other customers to help you out because reminder – you showed them how little you value the relationship – and more so, because a car with their name on it, has failed on the racetrack, potentially very public way. Shop B probably isn’t about to bend-backward to help you out either, because they don’t really know you.

Our parents knew this – it’s why they went to the same mechanic for 20 years, but it’s easy to forget in this age of Amazon that there are actual people on the other side of that transaction. That’s not to say you need to stick with the first shop you visit – just make sure you’re mindful of the precedent you could be setting when you make these decisions. And who knows, maybe you’ll build meaningful relationships, true enduring friendships. After all, like most communities, car culture has more with people than it has to do with cars.

All of that’s to say, I try myself to be there for Richard, because he’s there for me. Thanks to him, the FRS was back and better than ever. With our Mosport GP was just a day away, now it was my turn to perform. I knew I was enormously off-pace. Last year’s GT4 winner took the class win with a 1:40.578 in a Focus ST – meaning I was a whopping six seconds off the pace at our GP lapping day the week prior. The good news was that our Mosport GP weekend consisted of a practice day on Saturday, and a competition day, so I had some time to find pace on the still unfamiliar circuit. The bad news: one doesn’t simply find six seconds over a single lapping day. In any case, I wasn’t about to give up without a fight.

This is part five of a multi-part series. Check-in next week for part six!