It’s December, which means I’ve got nothing to do but sip coffee and day-dream about the upcoming track season that feels like it’s a thousand years away. By this point, I’ve literally put thousands and thousands of track miles on my FRS at a bunch of different race tracks. I’ve gotten to understand it’s chuckable character. The need to threshold brake into tighter corners while gradually feeding in throttle to rotate the car. How to balance the car using an early introduction of throttle on corner entry into long sweepers. How to deal with the FA20’s peaky nature through a set of deliberate and early downshifts. I’ve gone out with instructors, I’ve competed in competitions, I’ve analyzed and over-analyzed the data; you get the picture.

In doing so, I’ve involuntarily put together a list of things I would love to fix on the FRS. First is the stock seat – it’s great, but the faster I go, the sorer my knees get. Then there are the brakes. Even when running Glocs’ track-dedicated R10, I’m still managing to pull back into the pits smoking. The FRS’ stock suspension, which mind you is very, very good, has its limitations. With both upper and lower camber bolts, I haven’t managed to get more than 2.2 degrees of front camber, which has resulted in me chewing up the sidewall of multiple sets of tires. On a related note, the car simply doesn’t have that much lateral grip. Not enough to be objectively fast on a racetrack, and I can only be happy with the line, “fast for a stock FRS” for so long.

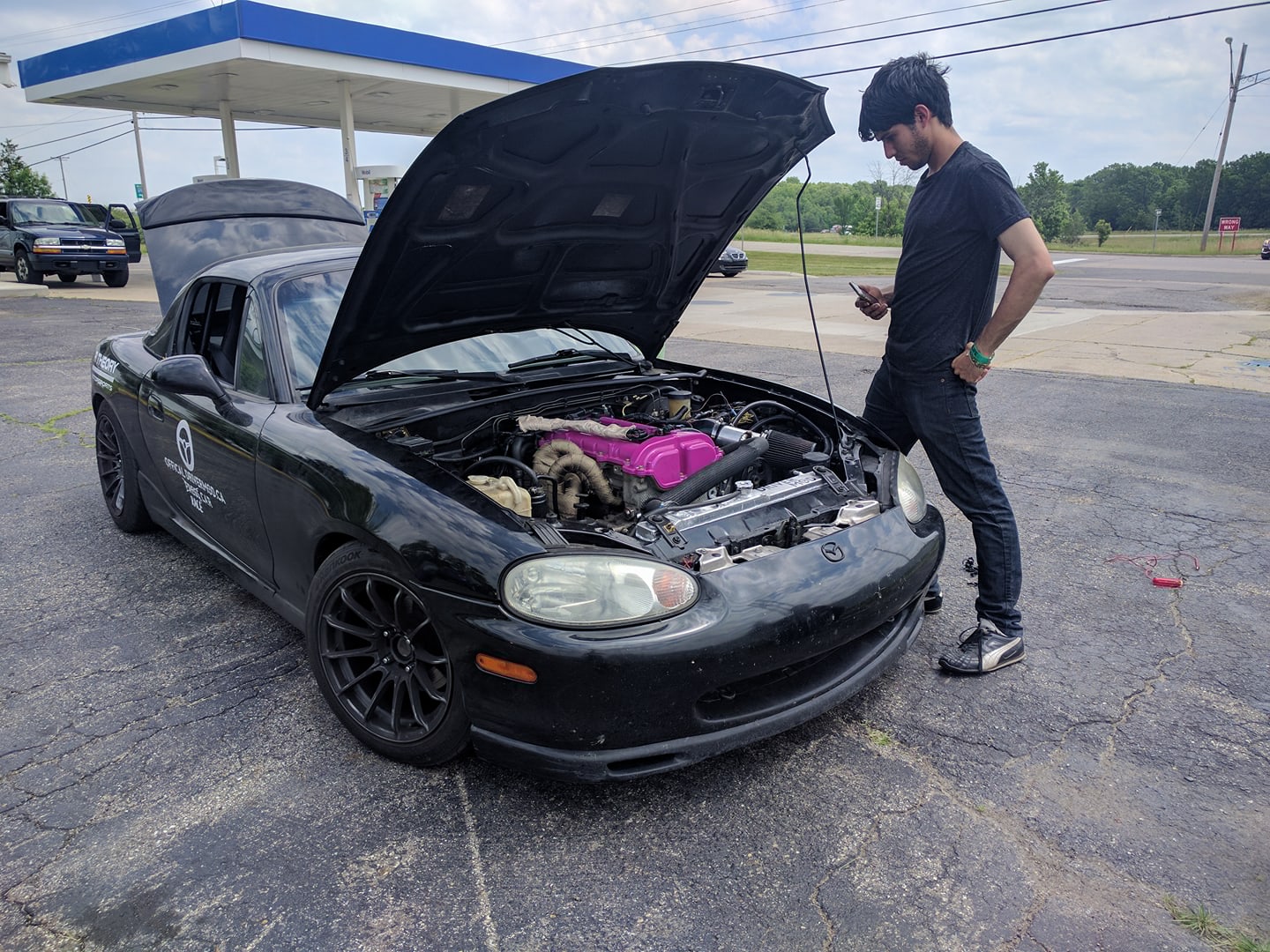

So here I am, putting together a mod list. Just like I did shortly before I ruined my last car; a 1999 Mazda Miata.

Why do we do this to ourselves?

We buy fun, friendly sports cars, and over the years gradually modify them until they become:

- Completely unreliable, resulting in never being able to drive them

- So expensive to own that the resultant financial stress ruins any fun you might be having.

This mostly happens because we’re simultaneously terrible at budgeting for all the little things a build is going to need, and completely incapable of budgeting for a worst-case scenario. As a result, we either cut corners resulting in complete unreliability, drain our bank accounts, or both.

Let’s say I wanted to turbo-charge the FRS. My initial budget would look something like this:

- Turbo kit

- Upgraded Radiator

- Upgraded Clutch and flywheel

- Larger oil cooler core

- Catback exhaust

- Dyno tune

That in and of itself doesn’t seem like that intimidating of a list. You save up the necessary funds, order yourself a boatload of parts and get to work — and the list of things you missed almost immediately starts piling up.

You forgot replacement exhaust manifold gaskets! Ah darn, this kit isn’t rated for use with stock fuel injectors so you’ll need to pick up a high-flow set. That turbo is sure going to get hot – I better invest in a turbo blanket. Oh no! I cracked the oil pan trying to weld on an oil fitting. I may as well pick up an aftermarket high-capacity pan. That exhaust manifold sure looks mighty close to my coil packs – better wrap it in some titanium exhaust wrap while it’s off the car.

While I’ve got the trans off the car, I might as well do a trans and diff fluid flush. My throw-out bearing is looking a little tired as well; let’s replace that. While we’re in there, these cars have notoriously weak clutch forks so let’s get that replaced. If I’m going to spend all this money on a dyno tune, I may as well invest in an electronic boost controller too. But wait! How am I going to monitor engine health on the track? Better pick up a gauge pod and some gauges.

All of this has happened before you even start the car, and before you know it – you’ve spent another five grand. The problem here isn’t that your logic for each of these additional purchases wasn’t sound – it’s that you didn’t have the experience or the foresight to anticipate them. But what if you did? You still can’t rule out the inevitable blown motor, broken transmission, shattered axles and busted differential that you’re bound to have to deal with at some point. Because that’s what happens when you double a car’s horsepower and track the shit out of it.

Project cars are truly great fun, but if you go into one with an optimistic budget and timelines, they can be – and I’m not exaggerating – soul-crushing. So how do you avoid this?

Toss out this idea of a vision

You can picture it so clearly – full aero package, shrieking exhaust note, an obscene amount of horsepower. Now I want you to take that vision – the parts list, the gushing excitement – and toss it in the trash, because you’re doing this wrong.

There are a few problems with the idea of a SEMA-style build. The first is that you don’t actually know what your car needs until you spend some time really driving it. That means thousands of miles of street, and preferably track driving on a stock car. Once you have a bunch of seat time, doing a ton of mods at once is generally inadvisable because you won’t be able to tell the effect any single mod had. As a result, you could be adding parts that actually make your car slower, but you’ll never know thanks to all the other parts you’ve added that are actually working. Doing one thing at a time also gives you time to re-learn the car as changes are made.

It’s also much easier on your wallet.

Be careful with mods that have dependencies

I spent a while debating whether or not I should try adding some naturally-aspirated power to the FRS. On these cars, a full exhaust and a tune will net you roughly 20 hp. Someone posted a Perrin catback for sale for a good price, and I nearly bought it. But then I considered the cost of the front pipe, over pipe, header, and dyno tune, and realized that I was on the path to spending $3000 to get 20 hp. When framed that way – the whole project sounded a lot less reasonable.

Another example of this is an airbag-less steering wheel. They’re great; they give your knees more room and they’re generally smaller, making your steering faster. However, a lot of time attack series’ require neck restraints (i.e., a HANS device) if you choose to use an airbag-less wheel. That means you’ll need a harness, which typically requires a roll bar, along with a bucket seat and it’s required mounts. All of a sudden your steering wheel has just cost you $3000 and a ton of streetability.

Before you buy anything, consider all of its dependencies when making your decision.

Twice the money, Three times the time

But what if you want to go forced induction? Doing one thing at a time will be impossible – as will avoiding mods with dependencies. The trick here is to come up with a theoretical budget and double it. I mean really double it, as in literally having 2x your budget in cash in your bank account. That way you won’t cut corners, you won’t end up eating ramen, or worse, borrowing money just to finish your car.

Also, everything will take longer than you expect. Even when you give your car to an incredibly reputable shop; it’s not uncommon for timelines to double. That said, if you’re going to do a build that’s going to put your car out of commission for a while, you need to have a reliable daily.

Final thoughts

The fear of putting myself into another five-figure financial black-hole has resulted in me being extremely conservative with this car; to the point where we ran it in Gridlife time attack at Road Atlanta on stock suspension. The result is that I was able to do over 20 events in a single summer without a single mishap.

Next year, we’ll be adding some grip courtesy of KW coilovers, improving the driving position by installing a Recaro Profi SPG seat, and we’re fixing our over-heating brakes problem by adding brake ducting. That should be enough to make the car a lot more competitive without compromising reliability or spending big-bucks on forced induction. The goal here is ultimately to build a time-attack car over the span of ten years. Later, we might replace sway bars, possibly add a shorter final drive, and we might even try to squeeze a 10-inch rim under these fenders. But the constant here is that we’re doing one thing at a time.

It’s not sexy, and it won’t make for great Youtube content, but it’s the only way I know to build a brilliantly fast car on a budget without ruining it altogether.