This is Part 4 of our multi-part series called “How to Win a Time Attack Championship”. You can read Part 3 here.

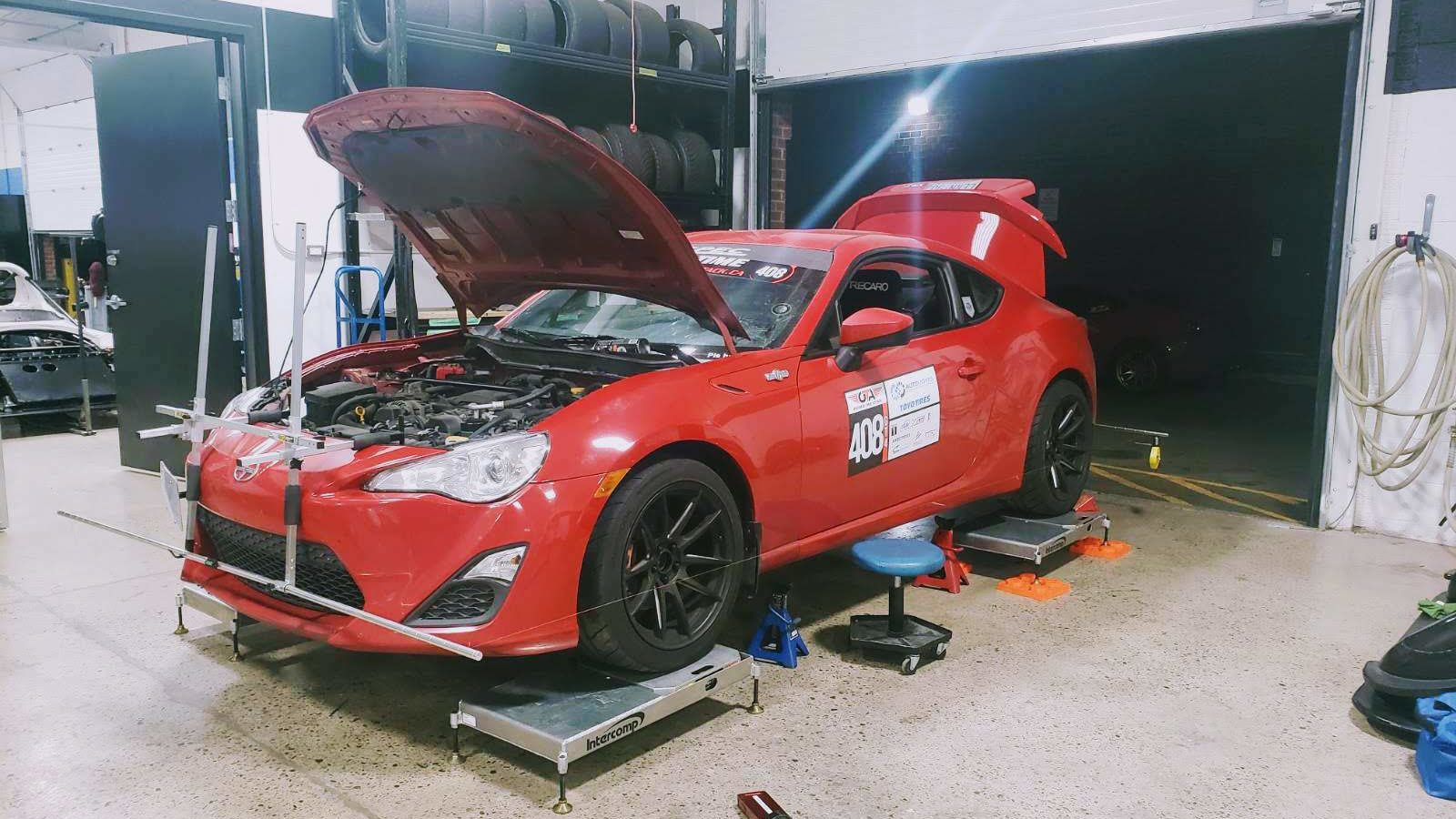

At the risk of stating the obvious, going faster meant two doing things: literally making the car faster, and becoming a more consistent, competitive driver. Ontario Time Attack’s impeccably granular classing system meant that there was little I could do in terms of actual mods. Doing virtually anything – from aftermarket swaybars, to lowering springs, to an intake would have punted me out of GT4 class. Instead, I focused on optimizing my alignment. This meant fixing its one glaring problem: front camber.

Racing the Rulebook

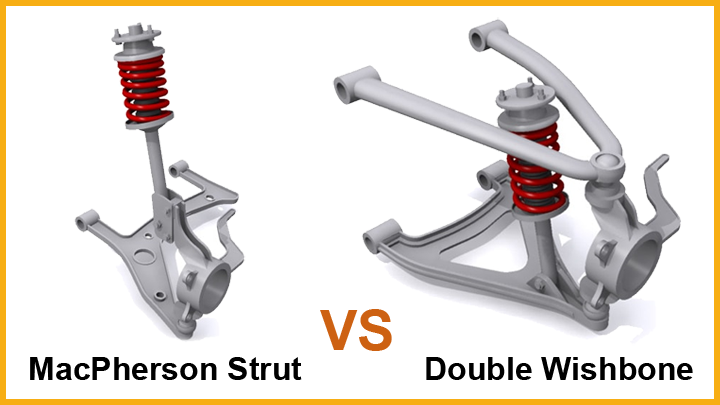

The front of the Scion FRS features a Macpherson suspension setup – meaning the wheel hub is connected to the chassis through a lower control arm, and a strut. Generally speaking, this isn’t a good thing. Most sports cars – Mazda Miatas, Honda S2000s, and alike – use a double-wishbone or multi-link setup, because they offer one significant advantage: they allow the wheel to gain camber under compression. That matters, because you’re gaining camber precisely when you need it: during cornering. The Scion FRS’ rear suspension however does use a multi-link setup, so it does gain camber under compression. All of this has the effect of producing every driving enthusiast’s nemesis: understeer. Not an issue with a factory alignment, but due to my setup’s limitations, I was running the same amount of front and rear camber.

* Note: Shockingly, nobody has posted FRS/BRZ camber curves online, so the above is based on generalizations and observations. If the concept of camber is confusing, check out our guide on camber.

Picture from cartreatments.com

Obviously reengineering the car’s front suspension is out of the question, so there was really only one solution to this problem: run an enormous amount of static front camber. We started with a pair of camber bolts which allowed us to run up to 2.5 degrees of front camber. We then tried slotting the front struts (i.e., turning the bolt holes into an oblong slot). That allowed us to add camber but resulted in another problem: my 17”x9” wheels started rubbing against the spring. Because reminder: the car was on stock struts and springs for classing reasons, and stock springs are wide.

Then we tried adding a wheel spacer – as doing so would add clearance between the wheel and the spring. This presented yet another problem: classing rules. See, there’s this line in the Ontario Time Attack rulebook pertaining to wheel fitment, that makes virtually no sense to anybody:

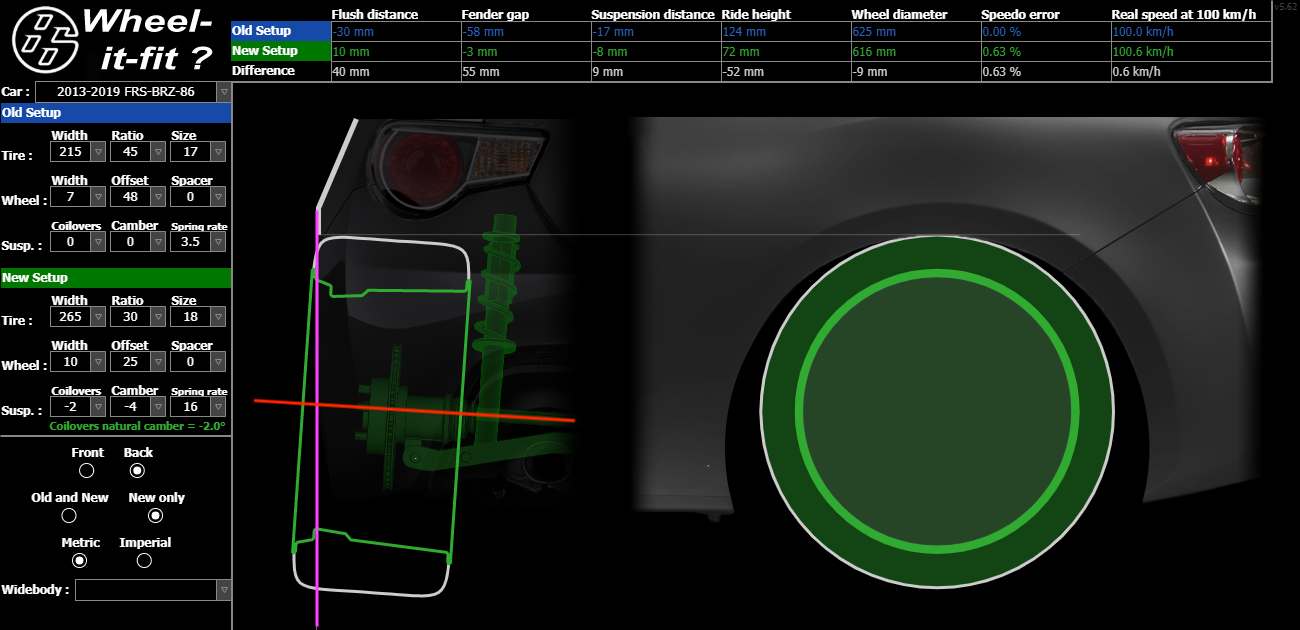

“The widest point of the tire, above the axle, does not protrude more than 13mm (0.5”) from the widest point of the OE wheel well opening when measured in a vertical plane coincident with the axle line.”

Bear with me while I try and explain this. In the diagram below, the wheel is outlined in green. Then there’s a second pink line: that’s a horizontal line traveling straight-down from the fender. If you were to measure the distance between that pink line, and the wheel, at the axle (shown in red), the wheel can’t extend past the pink line by more than 13mm.

Don’t ask me how to actually measure this – OTA’s method involves string, a weight, a ruler, and some math I’ll never understand. I used an online tool called “Wheel-it-fit?” (screenshotted above) to figure out what wheel fitment would be legal.

All of that is to say – slapping on a spacer and calling it a day was out of the question. Instead of moving the wheel, we would have to move the spring instead. That’s where Whiteline’s offset top hats come into the picture. They’re a cheap and simple way to add 0.5 degrees of negative camber Better yet, they use OE-style rubber so they wouldn’t impact my class.* Finally, we had roughly 3-degrees of negative front camber at our disposal.

* OTA has rules regulating top hat materials. They’ve been revised for 2021 to allow the use of pillow-ball adjustable top hats. TLDR; read your rulebook.

Driving Faster

On to the harder problem: actually driving faster. I realized pretty quickly that relying on practice sessions in the morning of competition day to, well, practice, is a bit like studying the morning before a test. For one, you’ll be way too amped up on competition day to get any sort of meaningful practice in. Secondly, you’ll almost certainly run into traffic. And finally, if you discover something you don’t like about the car, or worse, you break something, you’ll have no time to make repairs or adjustments. For all those reasons, getting out to the track for meaningful, consistent practice before every event – ideally, on a quiet day at the track you’ll be competing at – is mandatory.

The keyword here is “meaningful” because ripping laps on a Sunday night with your buds isn’t immediately going to make you faster. I’m talking about laying down consistent laps and getting faster with each session. At a minimum, this means having a lap timer in your car, preferably one that shows you the delta between your best lap and your current lap in real-time.

Our next Ontario Time Attack event was taking place at the Canadian Tire Motorsports Park. It was also the most personally problematic – I wrote an entire piece on how the famous circuit scares the shit out of me. It was also a track I had very little experience driving. If I was going to have a chance in hell of making it onto the podium, I was going to need practice.

Aside from being fast, scary, and dangerous, ripping laps at Mosport GP also presents a logistical challenge. Presumably because of the massive insurance liability associated with renting the track, most clubs that run events at Mosport GP want proof of experience before you’re allowed to drive the track. Which would be reasonable if any Mosport GP experience counted. Most clubs not only expect experience, but they expect you to have experience with them, which makes it difficult to shop around for lapping days if you haven’t been driving the course for a decade. Thankfully, JRP’s Speed Therapy isn’t quite that egregious.

Nathan and I hit up a Speed Therapy lapping day on a quiet weekday. At this point, Mosport GP was exceedingly new to me – I’d only driven it once prior. I knew all corners by name and had a rough idea of the line, but I was a long way away from being able to put down a competitive lap time. Nathan on the other hand was a Mosport GP veteran – he was really just there to make sure that the car’s new aero package worked.

I generally consider myself to be a fast-learner, but Mosport GP presented two significant challenges to me. First off – and forgive me for sounding like a broken record – it’s so damn fast. Nearly every corner features apex speeds over 100kph, some exceeding 150kph, in a street car. It’s fast in a way that makes every other circuit in Southern Ontario feel like childs-play. In short, it’s fast in a way that I just hadn’t experienced up until that point. With speed comes greater consequences. You can’t just toss the car into a corner 10 kph faster than you’re used to and hope for the best.

Generally speaking, once you’ve exhausted your own abilities, there are three ways to get faster: instruction, video, and data. Which one is right for you largely depends on your experience. Instruction is great if you’re either new to performance driving or unfamiliar with a given course. After all – what could be better than direct, turn-by-turn feedback provided to you in real-time? I specify that new drivers have the most to gain from instruction, not because experienced drivers won’t benefit from instruction, but because the benefits of instruction are limited by the abilities of your instructor. As you go faster, the pool of instructors who are both able to provide meaningful feedback specific to you and your car, and who are observant enough to spot the types of things that will find you two or three tenths in a given corner, becomes smaller and smaller.

One way to expand that pool of feedback is through video. Specifically, taking video at the track, overlaying it with data (i.e., throttle position, brake pressure, and steering angle), and sharing it with as many smart people as you possibly can. It’ll never be a replacement for one-on-one instruction, but it’s useful for getting a variety of opinions. And variety is good – because you’ll get a myriad of different things to try later. Some of it will be bad – my last driving instructor advised that I take every bit of driving advice (even advice from him) with a grain of salt. But some of it will work – and that’s where you’ll find time.

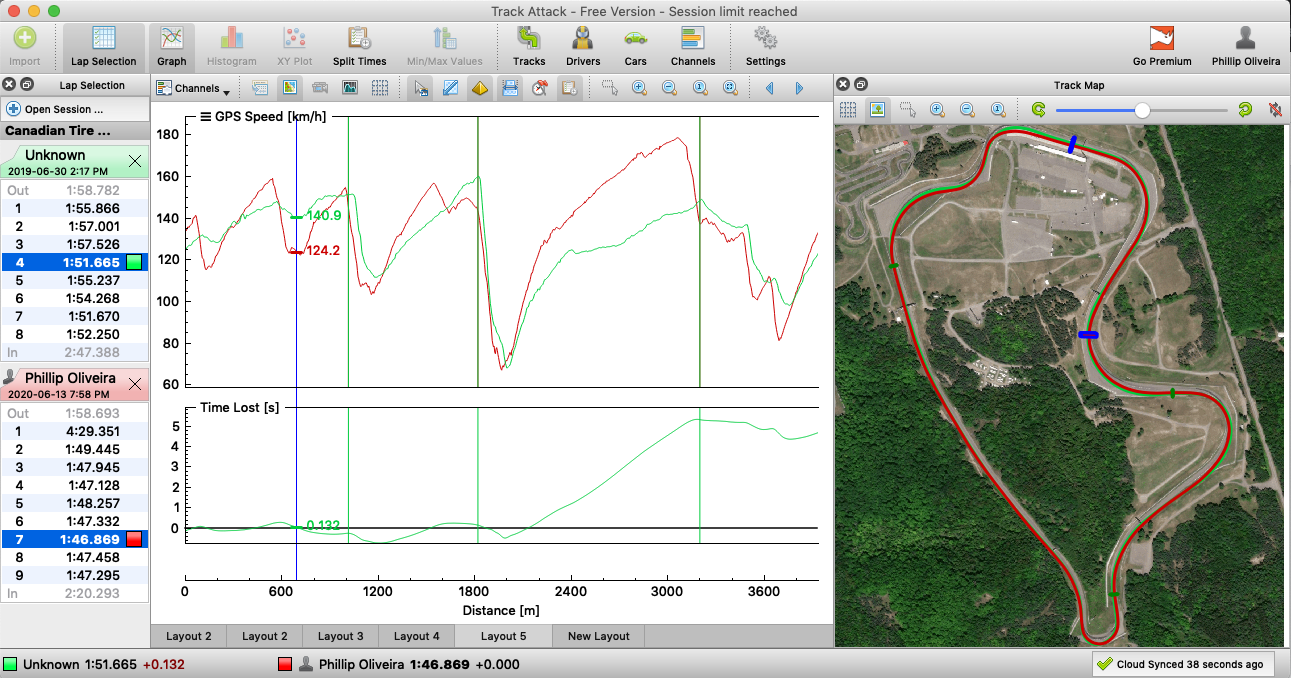

Chasing tenths is where data analysis starts to become useful. It has the advantage of allowing you to pinpoint precisely where you’re gaining or losing time on a given lap. A lot of people assume data analysis needs to be very complex and very expensive; it doesn’t. All you need is a smartphone, a 10hz GPS receiver, and an OBD2 reader (optional, but useful if you have a modern OBD2 equipped car). Load up your favourite lap timing app (RaceChrono is excellent) and you’ll have everything you need to compare speed, throttle, brake pressure, and your line, lap by lap. That will let you answer two questions very quickly: why am I off my pace today? (by comparing today’s laps to your personal-best lap) and why am I slower than my competitors? (if they’re willing to share data with you)

Note: for a more comprehensive look at how data analysis can make you faster, check out this piece.

After our lapping day at Mosport GP, I uploaded my fastest lap of the day to Youtube and shared it amongst as many smart people as I could. Kevin Wong, OTA’s chief timer, spent nearly an hour going over the video with me turn-by-turn, and provided me with a mountain of feedback. My line was off in some spots – driving slower tracks teaches you to apex late, always. Not the case at larger, wider tracks. In other areas I was inconsistent with my throttle and steering inputs. (To quote Kevin: “commit to the corner like she’s your fiance”) Most of my problems related to over-slowing, and conversely fear.

My friend Val was kind enough to pass me session data from some laps he did in his D-Series powered EG Civic, on 360tw tires. A car that should be slower than my FRS everywhere. That said, Val is a fantastic driver with literally hundreds of laps around Mosport under his belt. As a result, there were several sections where his mid-corner speed vastly exceeded mine. In short, it showed me exactly where I was over slowing.

We had just two weeks before our competition weekend at Mosport GP: two weeks to get in as much practice as possible. Thankfully, Ontario Time Attack’s Mosport GP weekend consists of a “test-and-tune” day on Saturday, with competition sessions taking place Sunday. That meant I’d have at least one more chance to attack Mosport GP and put some of this feedback to work prior to competition day. In the meantime, lapping days at the Toronto Motorsports park would need to suffice.

Unfortunately, with just days to go before competition, it was at one of those quiet TMP lapping days where the notoriously reliable FRS suffered its first major mechanical failure.

This is part four of a multi-part series. Click here to read Part 5!